[Note, this post originally appeared on ProductCraft]

It was 3 am, ten kilometers outside of Marjah, Afghanistan, and just a few nights after the start of Operation Moshtarak (the largest offensive since the fall of the Taliban). I was a 26-year-old Marine Intel Lieutenant, huddled with a platoon in some abandoned farmers’ huts on the main route into Marjah. In the dead of night and in the middle of the desert, we heard occasional explosions and gunfire in the distance. And we were delighted. The enemy was only following their most likely course of action, not their most dangerous.

Ten years later, while working for IBM as a product manager on API Connect, I was reading a blog post by our most dangerous competitor and had a familiar feeling. Why was that?

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.”

―Sun Tzu,The Art of War

I spent the first eight years of my professional life leading operations and intelligence in the US Marine Corps. Since then, I’ve studied business strategy and led product management initiatives. Some of the techniques from one context can apply well to the other, and this series is an effort to outline when and how they can.

The Three Lessons of Competitive Intelligence

There’s a long tradition of business leaders drawing on military thinking. Terms like “campaign, rally the troops, follow the leader, keep your powder dry, recruitment, etc.” permeate the business world. One of my professors at UNC Kenan-Flagler, Mark R. McNeilly, wrote an entire book connecting the writings of Sun Tzu and business.

I won’t be undertaking a full book’s worth of analysis here. But I would like to share a few points from my personal experience that echo across the two contexts. One of the most valuable areas of similarity is that of competitive intelligence. By studying both military and market intelligence, we can find three helpful lessons:

- Use maneuver warfare: Apply our strengths to our competition’s weaknesses.

- Understand the competition: Identify their strengths and weaknesses, predict what they may do, and plan how to respond.

- Know the limits: Understand where these military concepts can lead us astray in the PdM world.

Maneuver Warfare

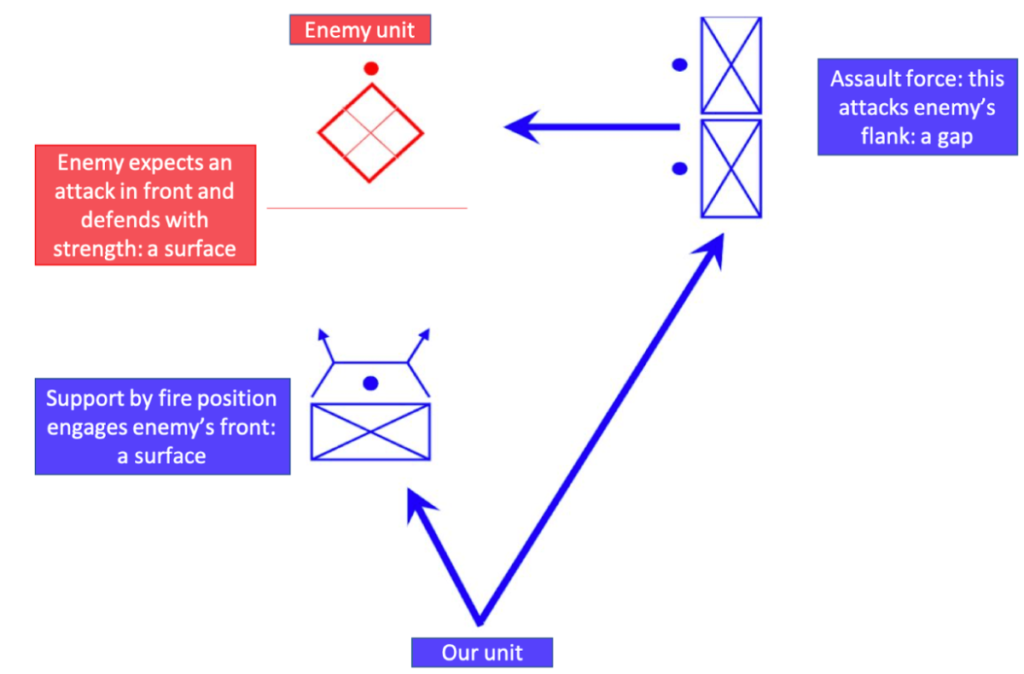

Unlike what you may have seen in war movies, military commanders don’t look at an enemy’s forces and shout “charge.” Attacking directly into the teeth of an enemy’s defense is a desperate, risky, and extremely difficult move. Instead, the vast majority of successful military leaders practice maneuver warfare. They look for “surfaces and gaps” in the enemy’s preparations. Then they maneuver their forces to concentrate their strengths against the enemy’s weaknesses.

“SURFACES AND GAPS. Put simply, surfaces are hard spots—enemy strengths—and gaps are soft spots—enemy weaknesses. We avoid enemy strength and focus our efforts against enemy weakness with the object of penetrating the enemy system since pitting strength against weakness reduces casualties and is more likely to yield decisive results. Whenever possible, we exploit existing gaps. Failing that, we create gaps.”

-Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1: Warfighting

Flanking the Enemy

In the Marine Corps, we invest heavily in training young officers in the principles and practices of maneuver warfare. These lessons are grounded in ancient military wisdom and tempered by the latest experience in combat. The simplest and most concrete example is a flanking attack. After locating an enemy, we engage them where they appear to be strong: their front (their “surface”) to control their attention, but then attack strongly where they are weak: into their flank (their “gap”).

Out-Maneuvering the Competition

When I interned as a PM at Amazon, I worked in the Marketplace Technologies Business. We helped third-party sellers sell their products on Amazon.com. For years, Amazon recognized eBay as a competitor. eBay was extremely strong at individual purchases. They could process payments easily, facilitate trust, and mediate transactions. However, they were much weaker at scaling that interaction.

Amazon met the minimum to match eBay’s surface: facilitating trust, processing payments, and facilitating search. Then they doubled down on their relative strengths: Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) as a service, Brand Registry to help protect sellers’ brands, advertising to help sellers position their products, and additional seller services to grow third-party sellers’ businesses.

There are many analogies we can use: surfaces and gaps, flowing like water through the best path, or the Judo strategy of using the “weight and strength of [your] opponent to [your] own advantage.” Regardless of which label we choose, it’s clearly preferable to reinforce your own strengths vs. a competitor’s weaknesses. However, you first need to know what these weaknesses are.

Understanding the Adversary

Military intelligence uses a set of frameworks, heuristics, and acronyms to quickly understand what an enemy is, what they are capable of, and what they are likely to do. While training as an Intel Officer, I studied military intelligence using templates based on the Soviet Army. The Soviets had an analogous organizational structure, goals, and tactics to our own forces. They had published doctrine and verified observations on how they behaved. And it was possible that one day we’d once again need to contend with a behemoth like the Soviet Union.

David and Goliath

Speaking of behemoths, a good analog for anybody working in technology is Amazon. Having spent time there, I can assure you that if you think you’re not competing with Amazon, you’ve probably missed something somewhere.

I saw this error once. After I finished my internship, I watched the founder of a startup that shipped subscription air filters pitch a room of fellow MBA students. One student asked, “How will you compete with Amazon?” The founder answered confusingly. He disputed that Amazon’s prices were lower (easily verifiable in a room full of laptops) and claimed that his startup would provide superior customer experience (possible). And he stated that Amazon was “too big and inflexible” to compete with his “nimble and scrappy” startup.

This last statement represented a potentially disastrous misunderstanding of the adversary. He viewed Amazon as a metaphorical Goliath when really it’s an army of Davids — numerous, nimble, and driven teams that can coordinate and scale.

Defining Your Enemy

Amazon is famous for its two pizza teams. Keeping groups small allows for autonomy and flexibility. In the Marine Corps, we would have called a two pizza team a squad (reduced). To describe an opposing group, we would use a SALUTE report, which specifies Size, Activity Location Unit Time, and Equipment.

In addition, we’d examine the adversary’s capabilities and limitations. Can the enemy DRAW-D: Defend, Reinforce, Attack, Withdraw, or Delay? Can the two-pizza team in Seattle match prices? Call in assistance from another team to enhance customer education? Could they withdraw from the market? Could they hold market share where it is?

After considering what an enemy can do, we need to consider what they’re likely to do. This is where we consider the Enemy’s Most Likely Course Of Action (EMLCOA). It’s important to have a plan to address an EMLCOA but also to think about the Enemy’s Most Dangerous Course Of Action (EMDCOA). To do this, we “turn the map around” and imagine what we’d do in the enemy’s position.

Analyzing the Enemy

As multiple battalions prepared to launch from our base for the invasion of Marjah, they prepared for the likely enemy reaction: improvised explosive devices and small arms fire. What really worried us Intel Marines, huddled around maps in our plywood huts, was what we knew we would do if we were in the enemy’s sandals. We would have rocket-propelled grenade launchers ready at all of the potential landing zones. Then we’d plan to down multiple helicopters as the invasion began. This would force Marines to respond hastily and recklessly — think “Black Hawk Down” but at a greater scale and with better-prepared defenses. Thinking this way led to detailed planning for dangerous contingencies — “turning the map around.”

Analyzing Your Competitors

An article by organizational psychologist Adam Grant outlines a technique used by Lisa Bodell where she encourages executives to “kill their company.” Imagine you are recruited by your biggest competitor and tasked with destroying your current company. This technique has been shown to unleash offensive creativity and reveal areas for improvement.

Years after my time in Afghanistan, I joined the product management team working on API Connect at IBM. Each PM had been assigned one or more of our main competitors to assess. By distributing the work, the team was able to put together the EMLCOAs of this set of adversaries. One of these was Amazon’s AWS API Gateway.

We determined that Amazon’s AWS API Gateway team would continue to drive prices down, provide basic function at scale, and maybe build out additional features. They would focus on their core strength: providing basic and essential levels of security to the native AWS APIs.

It turned out this assessment has been largely correct (so far). Amazon’s AWS API Gateway team has kept prices low, scaled geographically, and added some functionality to their basic strengths. What they have not done is take a radical EMDCOA: embracing hybrid cloud, on-premise data centers, and third-party cloud capabilities.

Pitfalls of Using These Techniques in Product Management

If a PM blindly applies these military techniques to the tech world, they will almost assuredly fail. These assessments are quite involved and time-consuming to do right even for one enemy. In the military context, there are few enemy organizations, often just one large one with sub-units.

In the product world, we typically have dozens of competitors. We can try to handle this like my PM team at IBM did, by splitting up competitors between PdMs. This can mitigate but not solve the challenge. API Connect alone has over fourteen direct competitors as assessed by industry analysts (though of course none of them come close to our capabilities 😉 ).

However, there’s an even more important problem than mere scale. In the business world, we’re not trying to kill anyone. Despite the militaristic jargon used in business, we’re actually engaged in trade. In trade, it is important to provide value to others. We must meet the needs of our users better than anyone else. Both military and product organizations have discovered that too much focus on the adversary can take attention away from where it really belongs: on the needs of the people we serve.

The Takeaways

Let’s summarize which 20% of the practices we’ve reviewed can deliver 80% of the value to PMs:

- Understand the strengths and weaknesses of your organization and those of your competitors. Remember the concept of surfaces and gaps. Apply your own strengths to your competitor’s gaps. Don’t try to become strong where they already are.

- Consider what the adversary’s team consists of, what their capabilities and limitations are, what their EMLCOA is, and most importantly, what their EMDCOA is. “Turn the map around.”Never forget that the real goal of a business is to meet the needs of our users.

- Don’t allow an obsession with your competition to replace an intense focus on the customer.

So, when I read that blog post about the AWS API Gateway why did I get the old feeling I had in that hut in Marjah? Because the competition was following their most likely course of action, not their most dangerous. At least not yet.

Mindfulness of these principles and of when, where, and how they can apply across contexts can enhance our competitive analysis. Try applying these heuristics the next time you’re evaluating the competition and let us know how it goes!